Catherine Rampell at the Economix blog of the New York Times (see here) has a post about the recent American Time Use Survey. Below is one of the summary graphs:

There are several interesting findings. The post states:

"Additionally, the less educated you are, the more TV you watched on the

average day last year. Americans with college degrees spent 1.76 hours

watching television on the average weekday, whereas high school dropouts

spent an average of 3.78 hours per weekday."

"God can have opinions; everyone else should bring some data." often attributed to W. Edwards Deming, but most likely should be attributed to R. A. Fisher or George Box

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Sunday, June 24, 2012

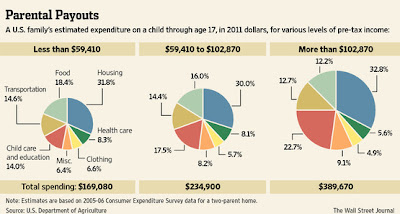

What kids cost

Carl Bialik over at the Wall Street Journal (see here) has an interesting post on what kids cost.

From the post:

"The real costs of raising a child for a moderate-income family"—including forgone income, college for those who attend, and the so-called opportunity cost of not investing the money—"would be closer to $900,000 to age 22 than the reported $300,000 expenditures to age 18," says John Ward, an economist and the president of John Ward Economics, based in Prairie Village, Kan., which consults on legal disputes for plaintiffs and defendants.

(The $300,000 estimate takes into account expected inflation. In 2011 dollars, the price tag for a middle income family is $234,900.)

From the post:

"The real costs of raising a child for a moderate-income family"—including forgone income, college for those who attend, and the so-called opportunity cost of not investing the money—"would be closer to $900,000 to age 22 than the reported $300,000 expenditures to age 18," says John Ward, an economist and the president of John Ward Economics, based in Prairie Village, Kan., which consults on legal disputes for plaintiffs and defendants.

(The $300,000 estimate takes into account expected inflation. In 2011 dollars, the price tag for a middle income family is $234,900.)

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Middle-aged and unemployed

The Wall Street Journal (see here) has an informative piece on the plight of middle-aged workers during the Great Recession. The author states: "As of May, the unemployment rate for people ages 45 to 64 was 6%, some

10 points lower than for people under 25. But the lower rate disguises

the fact that when middle-aged people lose their jobs, it's much harder

for them to find a new one. Those between 45 and 64 take almost a year

on average to find a job, more than two months longer than workers

between 25 and 44"

Friday, June 22, 2012

Bearing the brunt of the Great Recession

The Fiscal Times (see here) has a post highlighting some recent Census data that shows that Generation X may have experienced the most significant impact of the Great Recession in terms of median net worth.

The author puts it this way:

"Gen X, a generation that's relatively small at 46 million and known for their political apathy and trends like grunge in their heyday, has largely stayed out of the headlines; but they're also a generation that has tried to do everything right financially. Most worked at a stable job for years, built a comfortable savings, and likely just bought their first home at the market's peak. Then when everything came crashing down, they were stuck with an underwater mortgage, young kids in the house, possibly a job loss, and unlike boomers, they never had a chance to diversify their portfolios, potentially losing a lot of what they had in stocks."

The author puts it this way:

"Gen X, a generation that's relatively small at 46 million and known for their political apathy and trends like grunge in their heyday, has largely stayed out of the headlines; but they're also a generation that has tried to do everything right financially. Most worked at a stable job for years, built a comfortable savings, and likely just bought their first home at the market's peak. Then when everything came crashing down, they were stuck with an underwater mortgage, young kids in the house, possibly a job loss, and unlike boomers, they never had a chance to diversify their portfolios, potentially losing a lot of what they had in stocks."

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

Public sector employment continues its decline

The New York Times has an interesting article (see here) on the continued decline of employment in the public sector. Now I know there are many people who celebrate this (in fact, who seem to think that public sector employment is somehow "anti-capitalist"), but regardless of your view of the public sector, continued decline in employment there doesn't help the economy overall. The article's author points out that "If governments still employed the same percentage of the work force as

they did in 2009, the unemployment rate would be a percentage point

lower, according to an analysis by Moody’s Analytics. At the pace so far

this year, layoffs will siphon off $15 billion in spending power. Yale

economists have said that if state and local governments had followed

the pattern of previous recessions, they would have added at least 1.4 million jobs." See the chart below.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Interesting survey from the Economist

The Economist (see here) has the results of a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center that surveyed 21 countries. On the questions "Who is the world's leading economic power?", the results are given in the chart below:

Friday, June 8, 2012

New CBO report

The Congressional Budget Office has a new report "The 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook" (see here). The CBO is considered an unbiased and balanced source. The report contains the following graph (click to enlarge):

Timothy Taylor has the following to say about the graph (see here):

"Notice that before World War II, the highest points of federal borrowing--the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, World War I, and the Great Depression--were all below a debt/GDP ratio of 50%. World War II pushed the debt/GDP ratio above 110%, but then it dropped back down after a few decades. Even after the big budget deficits of the 1980s and early 1990s, the debt/GDP ratio didn't get above 50%. But the current debt/GDP ratio is now above 70%, higher than any previous episode in U.S. history other than World War II. The federal debt isn't in completely uncharted territory, but it hasn't visited this neighborhood often before."

Timothy Taylor has the following to say about the graph (see here):

"Notice that before World War II, the highest points of federal borrowing--the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, World War I, and the Great Depression--were all below a debt/GDP ratio of 50%. World War II pushed the debt/GDP ratio above 110%, but then it dropped back down after a few decades. Even after the big budget deficits of the 1980s and early 1990s, the debt/GDP ratio didn't get above 50%. But the current debt/GDP ratio is now above 70%, higher than any previous episode in U.S. history other than World War II. The federal debt isn't in completely uncharted territory, but it hasn't visited this neighborhood often before."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)